This rant is a bit random. This rant is very in the weeds. This rant is wonky and statutory-y. This rant is very on brand for me. If you do not enjoy my brand of ranting, would you please do us all a favor and unsubscribe? Because I love you and release you if you’re not into this. There are plenty of us who are ready to nerd out about super nerdy things together, and have a very good and derpy time with it, and honestly, some of you are just killing the vibe. It’s exhausting. Go and be free, or stay and be cool. The choice is yours. We are about to dork all the way out on several statutory provisions in the context of a bleeding edge edge case, and that’s really only for a certain kind of person, and it’s totally okay if it’s not for you. It probably means you are just sane and normal. That’s probably a good thing!

Coolio, weirdo, first of all, to reiterate — I’m about to riff along a largely unlikely-to-occur-in-reality path, as far as I can tell. You should not take this post as me delineating some probable outcome track. If you want to know what I think is going on with the case, in the main, you should read the last magnum opus. That’s still mostly where my head is. This is me going on a random walk for meditative purposes, thinking through some of the implications of § 242(d) and its convergence with some other interesting aspects of what’s going on (or, rather not going on) right now with AMC. Be smart, nerd out, and take it for what it is. Use your brain. This is an intellectual exercise. Ok? Ok. It does put some interesting glosses on some of the weirder aspects of the settlement arrangement that puts a few things in pretty fascinating relief, and will maybe allow you to see some things in a new light. Look, if you are interested, you’re interested. I don’t have to sell you.

Alright, so, if you know me at all, you know that I have been ranting and raving about things (in general) since the dawn of time, or probably at least since you’ve known me. Yep, I bet that checks out. Anyway, one of the things that I’ve been ranting about is § 242(d), which passed the legislature on June 30th, and which some of you are Very Enamored With™️ as is your right under the law to be, but I’ve had my doubts about its propriety, and frankly, have been giving the whole thing the stink eye from the get go.

In all of my thinking about § 242(d), I admittedly have been considering it to be something of a bogeyman. I have been imagining how someone at AMC or Nikola or one of these other companies probably paid some lobbyist some amount of money, because I assume that’s how these things work, and they got this law passed, because that’s how I assume those things work, and now they are going to use this law to dilute stockholders for the benefit of not-the-stockholders, because in the end, the stock market is a bit of a zero sum game (what’s that noise? do I hear the hedge fund bros coming? do you hear them? I think I hear them coming from above, let’s see if their comments talk down to me about how dilution is good even for retail stockholders who believe in HODL’ing like their life depends on it … natch, I’m sure I’m probably just imagining things…) Anyway, I admit it! I’ve been assuming that new § 242(d) would be used to stick it where the stockholders don’t see much sun shining. I’m sure that’s just the pessimist in me.

Also, for whatever reason, I’ve simply been thinking that there’s only one way to use § 242(d) here in the immediate future. Ok, to be fair to me, I’ve been being told repeatedly that there is no way to use § 242(d) here, and that it will have no impact on the currently-pending litigation or in the immediate near term, so I don’t even know why I’m even talking about it, but here I am, doing a stupid little girl thing for whatever stupid, silly little reason, and yet, for some ridiculous, inexplicable, incomprehensible raîson, y’all keep coming back and reading. In any case, why have I been so small-minded? Why have I been like a child, insistently trying to shove the square peg in the round hole, when instead you see those videos where the bird or the monkey or whatever allegedly lesser-brained creature will come upon the human’s game and sagely select the “wrong” wooden piece that actually fits inside the slot (the smaller circle through the square hole, for example), though it may not be the intended matching piece by geometrical standards, it is one that nonetheless can slide through the aperture.

Hmmmmm. Interesting.

What the &^&@*#$ am I talking about?

Excellent question.

Let’s back up a minute.

What if § 242(d) wasn’t going to be used to effectuate the exact transaction contemplated by the currently-pending settlement, if the currently-pending settlement were to be rejected by the Court? Because, that’s what I’ve been worried about, because to me it seemed like an end run around the settlement consideration. And that’s why I felt that it was absurd to say that § 242(d) would not have an impact on the currently-pending litigation, when the Vice Chancellor really could not help but contemplate the (potentially largely negative) impact of any potential requisite changes to the settlement that could trigger a termination right. But … it turns out, there are a lot of assumptions underneath all those conclusions.

To even begin to unpack all that I’m thinking about here, let’s step back and do something that I should have done weeks ago and re-print the Synopsis of HA1 to SB114, which was the Proposed Amendment to the Proposed Amendment to the DGCL, which attempted to cabin SB114 to the actual language of its original synopsis, to make it do only what it originally said it was going to do.

Please, read, and learn.

And remember, this proposed amendment to the proposed amendment was trying to make the original proposed amendment to the DGCL that just passed (SB 114) not so potentially broadly dilutive. This amendment to the amendment failed, so now SB 114 is going into law with potentially dilutive (I mean, re-lutive, how about z-lutive, or rather … wheeee-lutive!) powers, and this synopsis will explain the whole situation to you. It will explain what could have been, and in so doing, you will understand what now is, because the things that this amendment was trying to prevent? Well, (soon) they are happening (including the grammatical error that is now forever ensconced in the DGCL). C’est la vie, c’est la démocratie, and you should be educated, so here goes.

This Amendment conforms the language that Senate Bill No. 114 adds to § 242 of Title 8 to its stated intent, which is to allow companies facing a threat of delisting to engage in a reverse split by meeting a lower threshold for the required stockholder vote. As is fully explained below, this Amendment prevents SB 114 from creating an indirect method for a corporation to free up more authorized shares that can be dilutive to existing stockholders. This Amendment also corrects an instance of the word “affects” to “effects” and makes corresponding changes to the internal designations within § 242(d)(2) of Title 8.

“Shares outstanding” are the total number of shares held by all stockholders. A stockholder’s ownership in the corporation is a fraction reflected by the number of shares held divided by the number of shares outstanding. If a stockholder owns 100 shares and there are 1,000 shares outstanding, then the stockholder owns one tenth of the corporation.

“Authorized shares” are the number of shares that a corporation can issue. A corporation that has 10,000 authorized shares and 1,000 shares outstanding can issue another 9,000 shares. “Headroom” is the difference between the shares outstanding and the authorized shares.

Existing stockholders care about headroom because the issuance of more shares dilutes their ownership. If the corporation with 1,000 shares outstanding issues another 1,000 shares, then the stockholder who owns 100 shares (which previously represented 10% of the shares outstanding) will continue to own 100 shares; however, because of the additional issued shares, the stockholder's proportionate ownership of the corporation has been reduced (now represents 5% of the shares outstanding). If the corporation issued shares as part of a transaction that increased its overall value, then the stockholder may now own a 5% stake that is worth more and may have come out ahead. If not, then the stockholder has lost value, so the stockholder’s stake has been diluted.

The more headroom that a corporation has, the greater the risk of dilution is for stockholders. Due to the significance of authorized shares, Delaware has always required the vote of a majority of the outstanding shares to increase the authorized shares. A corporation must ask all of its stockholders for permission to create more headroom, since it can be used to dilute the stockholder’s shares.

Under SB 114, § 242 will allow a corporation to engage in a reverse split that reduces the number of its issued shares by a majority vote of the stockholders who participate in person or by proxy at a meeting. That standard is known as a majority of a quorum. For a public company, the number of stockholders who participate in person or by proxy at a meeting is always less than the outstanding shares. At most, only 80-85% of outstanding shares participate in person or by proxy at a meeting. SB 114 thus permits a reverse split by a majority of a quorum rather than a majority of the shares outstanding.

SB 114 is intended to address a problem that some corporations have faced when they risk delisting because their stock price is too low. To increase their stock price, they wish to engage in a reverse split, but cannot get the votes necessary to approve a reverse split by a majority of the shares outstanding. Under SB 114, § 242 allows a corporation to engage in a reverse split with a majority of a quorum.

However, as provided under SB 114, § 242 is not limited to only situations when a corporation is at risk of delisting because of a low stock price. As such, under SB 114, § 242 also enables a corporation to use a reverse split approved by a majority of the quorum to create headroom.

For example, if a corporation has 400 million issued shares and 500 million authorized shares, then a corporation has 100 million shares of headroom, equal to 25% of the outstanding shares. Existing stockholders can be diluted by another 25%. Under SB 114, the corporation can engage in a reverse split with a majority of the quorum by combining every 4 outstanding shares into 1 outstanding share, thereby reducing its issued shares from 400 million to 100 million. The 500 million authorized share number remains unchanged, so the reverse split creates 300 million additional shares of headroom, for a total of 400 million shares of headroom. That is equal to 400% of the outstanding shares, post-reverse split. Existing stockholders can now be diluted by 400%.

In addition, SB 114 allows a corporation that has one class of common stock to engage in a forward split and proportionately increase its authorized shares without a stockholder vote. For example, a corporation could start out with 100 million shares outstanding and 125 million authorized shares. The corporation has headroom of 25 million shares, meaning existing stockholders can be diluted by 25%. SB 114 would allow the corporation to engage in a forward split without a stockholder vote, in which each outstanding share divides into 4 shares and increases the authorized shares proportionately. After the forward split, the corporation is in the same position as in the example above. It has 400 million issued shares and 500 million authorized shares. It has 100 million shares of headroom, and existing stockholders can be diluted by another 25%. Under SB 114, the corporation can then engage in a reverse split with a majority of the quorum by combining every 4 outstanding shares into 1 outstanding share, thereby reducing its issued shares from 400 million to back down to 100 million. The 500 million authorized shares remain unchanged, so the reverse split created a total of 400 million shares of headroom. Stockholders started out owning 100 million shares in a corporation that could be diluted by only 25 million shares, representing another 25%. But through this 2-step process, after only a single vote by a majority of the quorum, stockholders end up owning 100 million shares in a corporation that can be diluted by another 400 million shares, for another 400%.

Reverse splits have always had the effect of creating more headroom, but they have always required a majority of the outstanding shares to vote. SB 114 reduces that voting standard to only a majority of the quorum without sufficient justification for doing so. Without this Amendment, SB 114 will allow a corporation to create more headroom with a vote of only a majority of the quorum, and to do so regardless of whether the corporation faces a threat of dilution.

This Amendment corrects this problem by making the following 2 changes:

1. Adds language limiting the use of § 242 to a situation involving the risk of delisting, requiring that "the corporation has received a delisting notice from such national securities exchange and such amendment becomes effective before the final deadline to cure in the delisting notice.”

2. Provides that a corporation can only use § 242 to engage in a reverse split if the number of authorized shares is reduced concomitantly.

Thus, this Amendment simultaneously addresses the 2-step transaction in which a corporation engages in a forward split to increase the authorized shares followed by a reverse split to create headroom because the authorized share number goes up and down concomitantly each time. If a corporation has 400 million issued shares and 500 million authorized shares and the corporation engages in a reverse split with a majority of the quorum voting, by combining every 5 outstanding shares into 1 outstanding share, the corporation reduces its outstanding shares from 400 million to 80 million, and the authorized shares are reduced concomitantly from 500 million to 100 million. Before the reverse split, the corporation had 100 million shares of headroom, equal to 20% of its authorized shares and 25% of the outstanding shares. After the reverse split, the corporation has 20 million shares of headroom, equal to 20% of its authorized shares and 25% of the outstanding shares.

Setting aside the key substantive piece of the proposed amendment that would have actually limited SB 114 to actual instances of reverse stock splits necessitated by delisting notices (as the original summary claimed the amendment was proposed to address), I think the proffered restructuring of the statutory construction for parts (B) and (C) would have made the overall construction of the statute better, but alas, the original passed into law in its as-is form, which is … pardon my French … clear as merde. But it’s probably just me.

Now that you have the background context on what the amendment does, let’s look at the language of the amendment itself.

The language (as passed) reads as follows:

(2) An amendment to increase or decrease the authorized number of shares of a class of capital stock or an amendment to reclassify by combining the issued shares of a class of capital stock into a lesser number of issued shares of the same class of stock may be made and effected, without obtaining the vote or votes of stockholders otherwise required by subsection (b) of this section if:

(A) the shares of such class are listed on a national securities exchange immediately before such amendment becomes effective and meet the listing requirements of such national securities exchange relating to the minimum number of holders immediately after such amendment becomes effective,

(B) at a meeting called in accordance with paragraph (b)(1) of this section, a vote of the stockholders entitled to vote thereon, voting as a single class, is taken for and against the proposed amendment, and the votes cast for the amendment exceed the votes cast against the amendment, and

(C) if the amendment increases or decreases the authorized number of shares of a class of capital stock for which no provision has been made pursuant to the last sentence of paragraph (b)(2) of this section, the votes cast for the amendment by the holders of such class exceed the votes cast against the amendment by the holders of such class.

I’ll try to also set aside my gripes with its substance, because I’ve covered them enough, and apparently, they did not carry the day. Fine. I’ll get over it. Maybe. But now, I actually have a bigger concern that I have failed to articulate because I’ve been so focused on substance.

So, here’s the problem. The structure of the thing is pretty freaking weird. It says, in essence, “you can do an amendment […] without obtaining a vote [under § 242(b)] if: [Y =] (A) + (B) + [(C) if X when not Y], where A = shares are listed/meet listing reqs; B = meeting + all vote + C = class vote (if increase/decrease [X] and no (b)(2) provision [Y].

Just so we’re clear (as mud), the “if” clause relates to “if the amendment increases or decreases the authorized number of shares of a class of capital stock for which no provision has been made pursuant to the last sentence of paragraph (b)(2) of this section” and the “last sentence of paragraph (b)(2) of this section” is as follows:

“The number of authorized shares of any such class or classes of stock may be increased or decreased (but not below the number of shares thereof then outstanding) by the affirmative vote of the holders of a majority of the stock of the corporation entitled to vote irrespective of this subsection, if so provided in the original certificate of incorporation, in any amendment thereto which created such class or classes of stock or which was adopted prior to the issuance of any shares of such class or classes of stock, or in any amendment thereto which was authorized by a resolution or resolutions adopted by the affirmative vote of the holders of a majority of such class or classes of stock.”

I notice now that this is even more confusing in a way that doesn’t matter here, but that (C) only applies to increase and decrease, not to reverse split per se (because it lacks the “reclassify by combining language” and a reverse split in itself doesn’t actually require an increase or decrease) so blessed be to anyone who actually has to litigate the meaning of this section if it becomes an issue, but isn’t that how these annual amendments got their nickname: The Full Employment Act for Lawyers? It needs to stop, we need to do better. But I digress.

Ok. Just to be clear, setting that distinction aside, what happens in a world where yes Y (as in, what if there has been a provision made under 242(b)(2))?

I think it’s pretty clear that C falls away as a requirement altogether. C is only a requirement if “not Y” (no § 242(b)(2) provision has been made) is the state of the world, and you are doing an increase or decrease. Agreed? Agreed.

Alright, now that we have the structure and basic outline of the statute in front of us, here’s the thing that I have been thinking about — what if we started from a blank slate and asked the following question, in good faith: what if § 242(d) were used to effectuate the best possible transaction for the benefit of (all) the stockholders and the company? That would be some whack thinking, now, wouldn’t it? I mean, I wouldn’t want anyone to sprain a neuron or anything. I know everyone just wants this thing to be over with, but really, shouldn’t we stop to consider the best way to end this?

One second, I’m getting a phone call. Oh, hey, it turns out Antara finally decided to get a subscription, and they don’t like where this is going. They must be more prescient than I gave them credit for. Well, anyway, it’s a good thing I don’t take song requests. (Just kidding, I don’t think they were smart enough to subscribe, I’m doing a bit, but seriously, I don’t think Antara is going to like this suggestion, but given that 100m APE 0.00%↑ sale the other night, they may no longer have any skin in the game.)

Look, I’m always going to be pissing someone off in war-gaming these things out, that’s the nature of this game. I’m surely not paid to try to achieve specific outcomes, I see my job 100% to run up and down the lawful-true-chaotic neutral band in trying to be an arbiter of justice, to make sure that the legal system is in check with reality, and to always make sure that we are trying to get to the actual truth of the matter. I’m not here to see anything through except a thorough, intellectually-honest investigation of what’s possible, and happily, the game I’m playing is not to make any one contingent happy. The game I’m playing is to spitball about legal things, and nerd out about the law. The fact that somebody showed up and started playing some absolutely perverted financial crimes, er, I mean, games, in my backyard does not make it my problem that I have to figure out how to make you all happy. And even if I wanted to make you all happy, there is absolutely no way that I could ever do so. So, suck it up, buttercups. Some days you’ll love my hypos, some days, you’ll hate them. It’s just like law school: some days you get cold called, other days, you get passed over when you’re desperate to show off that you know the answer because you actually did the homework. You survive. Anyway, I’m not even the professor, I don’t assign your grades, I’m just some gunner sitting up in the cheap seats chirping and heckling at the refs and the teams, trying to make sure everybody plays fair and the concessions aren’t overcharging you. Just let the metaphor go. It’s overextended.

Look, let’s, maybe one more step back to see where what we already have on the record about § 242(d), because it’s confusing af, and unwinding it to see what’s possible seems required. Ok, I’ll be honest. Here’s the real thing I’m struggling with that is in the background of my mind: I admit to being absolutely unable to comprehend what the Special Master was talking about in this part of the Report and Recommendation, where she said the following:

The Delaware Senate recently approved a proposed amendment to Section 242(d). If passed, the revised statute will provide that “[a]n amendment to increase ... the authorized number of shares of a class of capital stock ... may be made and effected” by “a vote of the stockholders entitled to vote thereon, voting as a single class, [] taken for and against the proposed amendment, and the votes cast for the amendment exceed the votes cast against the amendment,” subject to other conditions not relevant here.

Ok, so far, so uncontroversial.

But then:

The proposed amendment does not modify the specific statutory language at issue in this case. However, at least one Objector argues that, in light of the proposed amendment, “it makes sense to deny this settlement and let AMC go about this the right way,” and “without their illegal 4-D chess shenanigans.” This is not a viable alternative because it assumes that Plaintiffs could achieve complete success on the Section 242 claim and convince the Court to invalidate the entire APE issuance—a result that stockholders achieve rarely, if ever.

The first sentence is true, as far as it goes, although such argument has been (enragingly) used to argue that these statutory changes to the DGCL would not have an impact on this pending litigation, which — I think — we should be able to put to bed at this time, for the love of g-d. Yes, you can parse the fact that what gave rise to this litigation is not what is being addressed by the proposed statutory amendments to the DGCL, but the remedies proposed by the settlements are almost precisely on all fours with the proposed statutory amendments to the DGCL, it just so absolutely happens in what is I’m sure an entire freaking coincidence of entirely no consequence or derived meaning. But in any case, What I really do not understand is what the Special Master means when she says that Ursa’s proposal is “not a viable alternative because it assumes that Plaintiffs could achieve complete success on the Section 242 claim and convince the Court to invalidate the entire APE issuance—a result that stockholders achieve rarely, if ever.”

Remember that Ursa’s proposal was for the Court to deny the settlement and to “let AMC go about this the right way.” In their public-facing filing, they don’t provide any further color or detail about what this means, or how it would work, so it’s difficult to parse why or to what specific extent the Special Master’s response does or does not comport with my specific understanding of the statutory provisions, so, buckle up, we’re going to drill this down to the ground, and walk through it step-by-step.

When the Special Master says “this” is “not a viable alternative” — the “this” is presumably hand-waving to the entire concept of AMC terminating the settlement and doing some other deal to “go about this the right way.” And to be fair, when I’ve been considering the options on that kind of front, as I have foreshadowed above, I have considered them kind of taking the existing transaction and trying to shove it through the new portal of § 242(d). Now, I’m confused as to why that would be a problem on the Special Master’s read of both the skeletal plan laid out by Ursa and the convoluted construction of § 242(d)(2), but she explains that the problem lies therein “because it assumes that Plaintiffs could achieve complete success on the Section 242 claim and convince the Court to invalidate the entire APE issuance—a result that stockholders achieve rarely, if ever.”

But why would these two things be necessary predicates to taking this offramp and utilizing § 242(d)? If anything, as I have frequently argued, wouldn’t it be exactly the opposite concern? Wouldn’t the claim that was way more likely to remain be the fiduciary duty claims (because they are certainly not impacted by the change to the statute, if any of the claims are at all, given the way that time only flows in one direction and all)? And also, achieving complete success on the Section 242 claim doesn’t seem like an enormous reach, tbh, especially after the colloquy at oral argument. But the second contingency is way more perplexing. Why in the world would it subsequently and also require the invalidation of the entire APE issuance to invoke § 242(d) as an offramp?

Here, I am completely puzzled as to the underlying logic, and there’s not much to go on, other than trying to reverse engineer what possibly could have been the read that led to this logical outcome. How could it be that someone could think that APEs would have to be invalidated as a class of stock in order for § 242(d) to be used as an offramp in this situation? Presumably, and I’m just trying to game this out in my mind, but … I suppose if you thought that somehow § 242(d) could not apply if there was another outstanding class of stock beyond common, maybe? Like, that it could only work if there was a single class? I’m really reaching here, because I don’t understand, and I don’t understand even moreso because when she synopsized the statutory language in the first paragraph, she only included the § 242(d)(A) and (B) parts, and what I’m about to talk about really does logically implicate aspects of that confusing (C)—>if X when not Y business, but she didn’t include that in her truncated and abbreviated version, so maybe there’s another read altogether that I’m missing. Because she did say, when clipping out the (C)—>if X when not Y aspect, “subject to other conditions not relevant here.” So, I don’t think she could have been misreading C in any meaningful way that would have led her to think that APEs would have had to be invalidated as a class (and I’m not even sure how you could misread C to require that anyway), so what could possibly have led her to the conclusion that the APEs would have had to have been invalidated for the invocation of § 242(d) to be effective here? What am I missing? I honestly do not have a single clue.

Let’s walk through it slowly.

Ok, so. Have you seen Lemony Snicket? This is where I put my hair up in a ponytail.

The Status Quo Order is in place. It is holding in abeyance the results of the March 14th vote. Let’s make it even clearer. Let’s look at the specific language of the order, which states:

A. The Actions shall be expedited;

B. AMC Entertainment Holdings, Inc.(“AMC”) shall be entitled to hold its March 14, 2023 special meeting and solicit and tabulate any votes in connection therewith. AMC shall tabulate and disclose abstentions and votes cast pursuant to instructions received from holders of AMC Class A common shares.In tabulating votes corresponding to AMC Preferred Equity Units (“APEs”), AMC shall separately tabulate those abstentions and votes affirmatively cast pursuant to instructions received from holders of APEs and those abstentions and votes cast on a mirrored basis pursuant to the Deposit Agreement entered into by AMC and Computershare Inc.on August 4, 2022; and

C. Defendants shall not amend AMC’s certificate of incorporation as a result of any vote of shares at AMC’s March 14, 2023 special meeting (or any adjournment thereof), pending a ruling by the Court on Plaintiffs’ to-be-filed preliminary injunction motion;

IT IS ORDERED this 27th day of February, 2023:

The Court hereby sets a preliminary injunction hearing on April 27, 2023, and directs the parties to prepare and submit a scheduling order governing a briefing schedule; and

The hearing currently scheduled for March 10, 2023 is canceled.

Ok, so far, no help on why the plaintiffs would have to “convince the Court to invalidate the entire APE issuance” in order to invoke § 242(d). I mean, let’s go back to taking a step back.

Let’s imagine that the Court denies the settlement. Let’s go to the Stipulation and check out the Termination Right. It’s in ¶ 24 on page 28 of the Stip.

Termination of Settlement; Effect of Termination

Plaintiffs (as a Plaintiff group that unanimously agrees amongst themselves) and Defendants (as a Defendant group that unanimously agrees amongst themselves) shall each have the right to terminate the Settlement and this Stipulation by providing a Termination Notice to the other parties to this Stipulation within thirty (30) calendar days of: (i) the Court’s refusal to enter the Scheduling Order in any material respect and such refusal decision has become final; (ii) the Court’s refusal to approve this Stipulation, the Settlement, or any part of it that materially affects any Party’s rights or obligations hereunder and such refusal decision has become Final; (iii) the Court’s declining to enter the Order and Final Judgment in any material respect; or (iv) the date upon which the Order and Final Judgment is modified or reversed in any material respect by an appellate court and such order modifying or reversing the Order and Final Judgment has become Final. For the avoidance of doubt, the Parties stipulate and agree that the Court’s refusal to lift the Status Quo Order in the Order and Final Judgment or any change to the scope or substance of the Releases provided for in this Stipulation and the Settlement would constitute a material change that gives rise to each of the Parties’ rights to terminate this Stipulation and the Settlement. (emphasis added)

As I have mentioned previously, there’s a very clear avoidance of doubt clause that pretty much extinguishes any doubt about the effect of any attempt by Vice Chancellor Zurn to do any modification to the scope of the release here. Any such action will trigger a termination right.

So, let’s game it out just for the sake of argument. Let’s assume that happens. What then? Because it’s certainly not spelled out in the Report & Recommendation and I sure af do not understand how the Special Master reached the conclusion that she got to, so let’s play Chutes & Ladders and figure out where on the game board I fell in a hole and missed a chute or a ladder in the process of figuring out where this would all lead. Remember, we are way out in fantasy land playing children’s fake board games now in some other dimension of reality. We are just playing mind games. But let’s keep going.

So, the termination is triggered because let’s just say that the Vice Chancellor has a problem with something in the scope of the release, and the parties decide to say “hasta la bye-bye” instead of coming back to the table with changes. As I have also mentioned previously, there are a lot of good business reasons why this choice would be extra freaking stupid and not advisable (since the company should / probably / likely does want the judicial imprimatur of an actual release, and this is probably not what would happen in reality if the lawyers had anything to say about it, but lots of what has happened in this case to get us to this point could be said to fall into that category, so for the sake of argument, we might as well just indulge my brain and game it out.

OK, so the termination right is triggered. Then what? The next paragraph is generous enough to continue with further directives in that event. It’s almost as though someone contemplated that this kind of thing could come to pass. Lawyers, such doomsday adventists, gotta love ‘em.

In the event that the Settlement is terminated pursuant to the terms of the preceding Paragraph 24 of this Stipulation or the Effective Date otherwise fails to occur for any other reason, then (i) the Settlement and this Stipulation (other than this Paragraph 25 and Paragraphs 8, 10, 20, 26, 45, and 46 of this Stipulation) shall be canceled and terminated; (ii) any judgment entered in the Action and any related orders entered by the Court shall in all events be treated as vacated, nunc pro tunc; (iii) the Releases provided under the Settlement shall be null and void; (iv) the fact of, and negotiations and other discussions leading to, the Settlement shall not be admissible in any proceeding before any court or tribunal; (v) all proceedings in the Action shall revert to their status as of immediately prior to the execution of the Term Sheet on April 2, 2023, and no materials created by or received from any Party that were used in, obtained during, or related to the Settlement discussions shall be admissible for any purpose in any court or tribunal, or used, absent consent from the disclosing party, for any other purpose or in any other capacity, except to the extent that such materials are otherwise required to be produced during discovery in the Action or in any other litigation; and (vi) the Parties shall proceed in all respects as if the Settlement and this Stipulation (other than this Paragraph 25 and Paragraphs 8, 10, 20, 26, 45, and 46 of this Stipulation) had not been entered into by the Parties.

Here are the interesting things I see in this paragraph, which I would summarize as basically:

The settlement is off and everyone is going to act like it never happened;

The proceedings in the Action shall revert to their status as of April 2, 2023.

On March 29, 2023, Defendants withdrew their motions to compel Plaintiffs depositions, so hopefully we never have to revisit this diegesis and follow-up that I’m pretty sure ended up being more words than the brief itself, but beyond that, we were barreling toward the April 27th Preliminary Injunction hearing. Obviously, April 27th, 2023 is no longer in the future and there’s nothing a judicial edict can do about that, but basically what this is saying is that we would be back in litigation posture. I’ll mention one other thing that happened on March 13th, 2023 that could become relevant in this branch of our Choose-Someone’s-Screwed-Up-Adventure tree, which is that AMC filed a placeholder Motion to Dismiss on the day that such a responsive filing was due (answer or file a motion to dismiss), so that thing is out there sitting on the docket holding space for what could be a brief someday if it grows up to be a big boi instead of a deflated little thing that no judicial officer could truly take action upon in its current form, no matter how many YouTubers try to will it into happening.

Anyhoo, so we’d be back in litigation posture, with the Status Quo Order still in place, and with August 1st, 2023 in the future and SB114 awaiting the Governor’s signature in advance of that take-effect date, so one could imagine a scenario that looks a little different than whatever the Special Master had in mind, because actually … what does the current litigation really stop AMC from doing? The Status Quo Order only stops AMC from doing one thing, really, and that is:

C. Defendants shall not amend AMC’s certificate of incorporation as a result of any vote of shares at AMC’s March 14, 2023 special meeting (or any adjournment thereof), pending a ruling by the Court on Plaintiffs’ to-be-filed preliminary injunction motion;

Ok, fine. Let’s say that they throw that meeting out the window. Let’s say they say who gives af about the March 14th meeting? Let it burn. They’ll go back to the Court and file a motion to dismiss that might just be granted after all that we have been through, if needs be, idk. More than likely, though, they’d probably have to wrap this whole thing up in another settlement, so in any case … look, I’m not here making any friends by suggesting that this thing could potentially end without a $20+ million dollar payment to plaintiffs’ counsel, but luckily, I am not primarily here to make friends, and as much as I believe in The Delaware Way, I also believe that if people have any intellectual honesty, they will be truth seekers, and . Too many people around these parts are more concerned about winning a popularity contest and never pissing anyone off than they are about doing the right thing. But if I’ve told you once, I’ve told you a thousand times, that’s not what I’m here for.

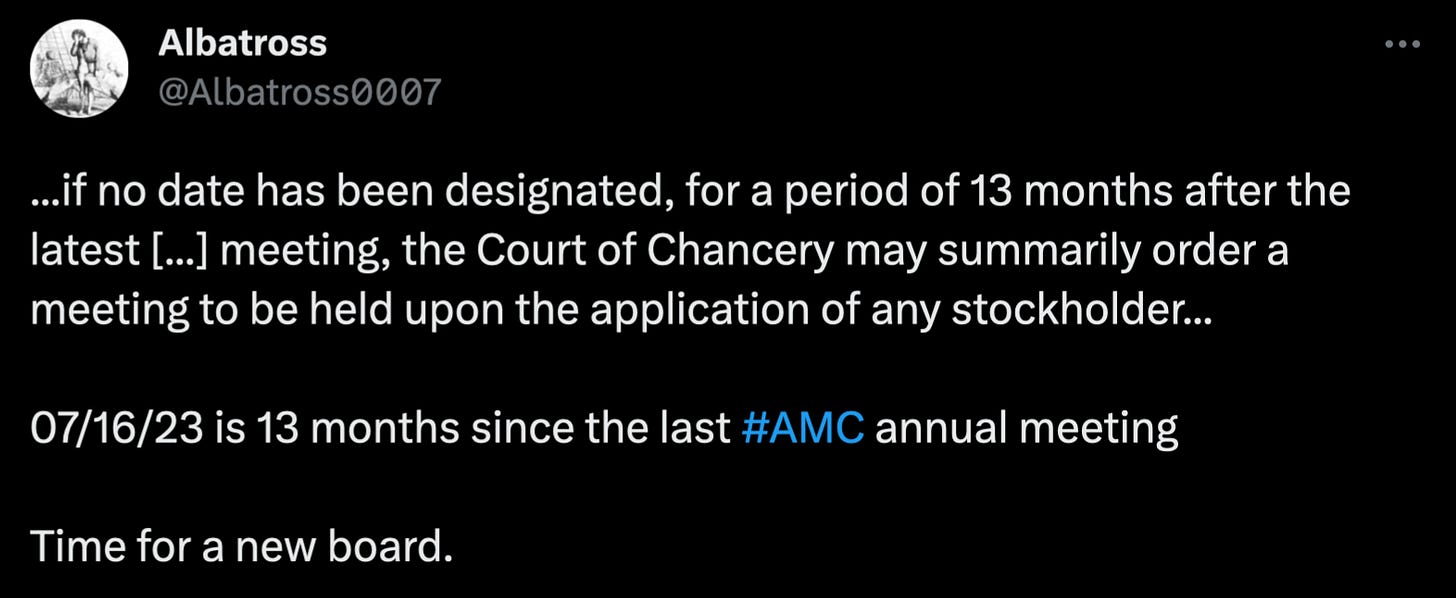

In the meantime, we’ll try to tee up a vote, because let’s say that they — I’m just spitballing here — when was their last annual meeting, anyway? I mentioned this several weeks ago on a podcast, but we’ve now reached the critical date, just so happens … yeah, happy noniversary! — it’s been thirteen months to the day since AMC held its last annual meeting. Huh.

Do you know what else that means? Someone on Twitter does!

Ok, since we are gaming out this situation, let’s take it a step further, since we are already taking about things that might require a stockholder vote, like, say, a re-do on those proposals from the Special Meeting in March, if — you know — you wanted to get them approved de novo. But wait. Did I remember nothing from what I said in the introduction to this piece? Let us not go rotely into that good night.

What if … let’s just say for the sake of argument … what if we were to consider other possible angles here other than just slotting in the currently-proposed proposals for the settlement? And again, I reiterate that some of you will not like some of these angles, we can be sure of that. I am not advocating for any one of these. I am merely presenting other possible things that could happen. For example, many people have said that they do not want to be diluted by preferred, and everyone has said harumph! good sir! there must be dilution by preferred, because without the reverse split and conversion of preferred to common, the company cannot solve its liquidity problems.

But, wait wait.

There’s one thing that I’m really good at, and that is asking questions like a five-year old (why? why? why? why? why? like a recursive function on autopilot), just to make sure that I really understand the predicate assumptions behind a conclusory statement, because sometimes there are a lot of assumptions in a brief statement, and you know what they say about those. Assumptions, that is. And I am asking these questions here in good faith, because perhaps there really is a reason, and I can be so sure that if there is, one of you is going to tell it to me in a needlessly condescending manner. And for every one of you who do it appropriately in the comments, two of you will do it weirdly or annoyingly by email. That’s just how the ratio works, I don’t make the rules. I still love you all.

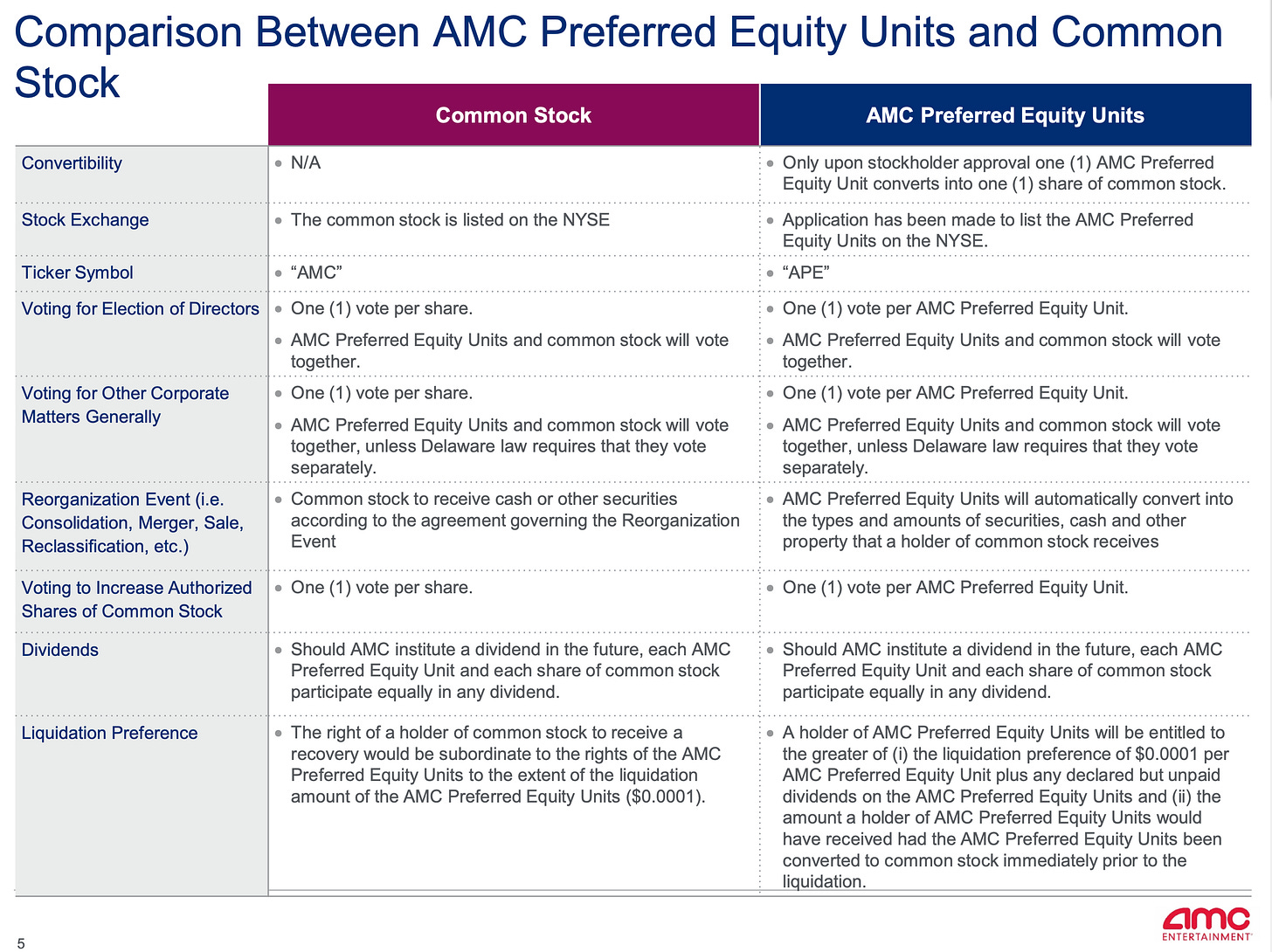

Ok, but here goes: why can’t the company solve its liquidity problems without converting preferred to common? Well, I’m sure that the people in an arbitrage position have all sorts of good reasons that we will undoubtedly hear in the comments below, vociferously and unlikely to be stated without some personal attack on my intelligence or other ad feminam kind of thing, but nonetheless, she persisteth. Mostly, I’m sure those reasons include that they would lose very large sums of money that they very much do not want to lose, or that they would not make very large sums of money that they would very much prefer to make, which, like, I totally get that. However, uh, those don’t particularly weigh on the scales of “what if we were doing what was best for the stockholders and the company qua stockholdings and company-ings” afaict, but feel free to enlighten me. I mean, I suppose if you are literally Antara and you say, I’m taking my ball and going home and will never do some sweetheart deal with you again if you stick it to me over here, and that wasn’t me that sold into the market the other night, I still hodl my 98m shares bro, if you welch on this deal, you’ll never raise capital with the bois club again, well … I guess you would just be probably revealing the true nature of how things work, and maybe that’s just something that we all have to come to terms with and stop being so PollyAnna-ish about. Could be. But in terms of what the actual purchasers of preferred stock writ large were explicitly promised and stuff, remember how the FAQ from late 2022 answered the question “Are the AMC Preferred Equity units convertible into common stock? If so, when?” with the answer “[Yes, but w]e do not currently expect the AMC Board to make such a proposal any time soon. It is more likely than not that the two securities, the common stock and AMC Preferred Equity units will trade as two separate securities for quite some time to come.” I know time travels fast in the meme age, but late 2022 really was not that long ago.

So, what if the company just … like … kept their word about that? What if APE just kept being a separate security for “quite some time to come”? Yes, yes, I know that some of your options would expire. Frank Iocono has made that quite clear and I’m sure he is not the only one who would have collateral consequences felt in the market.

But if common has to be diluted, why not by new money? Why does the call have to come from inside the building? Because what if § 242(d) was used to avoid the dilution of common by preferred, and instead to vote to on the reverse split alone? Because here’s what the reverse split does, if you read and understood the bit above about headroom:

Based on my last count, which might be slightly out-of-date, there were approximately 519,192,390 common shares outstanding and 995,406,413 preferred shares outstanding.

Let’s imagine that under the new § 242(d), a shareholder vote was held for just the common stock, to do a reverse split. Well, perhaps it could pass under the new, lower voting standard, and because it wouldn’t be coupled with a proposal to convert preferred into common stock. Let’s imagine that it passes. The way that a reverse split works is that you maintain the headroom shares as issued but not outstanding, in treasury. So, those are available to sell ATM, which everyone will now argue (and I will not disagree) can be accretive in value to the company and to its stockholders (everyone clap for this moment of unity). So, you have 51,919,239 common stock outstanding and 467,263,151 in treasury. Surely, that’s a sufficient amount of equity to play around with. And you still have 995,406,413 in preferred outstanding, but, like, okay, so what? Let them cook.

Now, this would mean that common stockholders would get no settlement consideration, but they also wouldn’t get diluted. They could have that accretive kind of share issuance where new shares are issued and sold into the market y’all are always going on about, which brings in new capital from external sources, but that should drive up stock prices, right? The same thing is not bound to happen with the dilution from preferred conversion, because — as we are told repeatedly in the affidavit of Loop Capital, and by logic itself — the market cap will remain the same, only the relative position of the stockholder classes will change.

Now, without a settlement, common stockholders would have no guarantee from the company that the preferred stock was actually not going to be converted for some period of time into the future, as originally promised. This will be a problem because the company can forward split without even holding a vote, so they could increase headroom in order to fit the APEs literally at will, so that kind of promise is something that would be a valuable as alternative settlement consideration, so maybe it’s an alternative settlement proposal to consider. And they can increase shares with a majority of the voting under § 242(d) or maybe an even lower standard as you’ll see below under § 211, but I guess my point is more just … they don’t have to do this exact thing that has been proposed. They don’t have to be like this. It’s obvious now that they can. They are basically set up to do whatever they want. But to present it like it’s required or some fait necessaire, it’s just untrue. And I’m just saying further that if you wanted to balance the Aquatic Safety kind of concerns where VCMR sua sponte raised the issue of the company creditors who were not being made whole by the settlement, and on that basis, did not approve the settlement as initially proposed (which would have bypassed the creditors and only paid off equity holders), one could consider an alternative. In Aquatic Safety, VCMR was worried about creating a fraudulent transfer claim by approving the settlement, and I put myself in a bit of a vortex thinking about how any dilution claims are being waived (along with every other claim under the sun) and that the act of the settlement itself is in fact the potential infliction of the harm, under one view of the thing, just as it would have been in Aquatic Safety, which was what troubled VCMR so much. Internecine wars among stockholder class members are the worst, y’all. Creating situations that pit classes and their interests against each other should be some de facto breach of a duty, I stg. It ain’t right. A corporation divided cannot stand, and yet here we are, trying to keep this thing propped up, and also avoid the whole thing falling down in the meantime.

Anyway, setting aside the issue of settlement consideration or no, or even whether or not we are talking about the terms of a settlement proposal or other third thing, there is this possible world where there is some other outcome under § 242(d) beyond just “plug and play the existing settlement arrangement” and for some reason, I just wasn’t creative enough to see it. I was blinded by my own concern that it was being weaponized against stockholders to imagine how it might be used for them, until I finally took a second to stop and think about it from its component parts. I admit that I am no closer to understanding what the Special Master meant when she said that the APEs would have to be invalidated in their entirety, unless it’s just predicated on a fundamental misreading of the obfuscatory drafting of § 242(d)’s construction, idek.

Because what if … just imagine … what if the company doesn’t actually want to extract unnecessarily value from its stockholders? I admit, I’ve kind of been riding on a sort of undercurrent presumption that they have. I mean, Adam Aron literally bragged about saving Wanda $25 million at the expense of minority stockholders in the last AMC case I covered, it isn’t like I’m not operating on facts here. But I’m willing to set that aside for now.

Maybe he has learned his lesson. Maybe he has changed his tune. Although to be fair, he has another reason to perhaps dislike this outcome, but also good policy reason to suck it up: because he, like the other executives (I have heard but not personally confirmed) have a large part of their compensation in preferred shares. This actually seems like an excellent alignment of incentives for them to keep the stock price high, fundamentals running solid, and even gives them the bankruptcy protection of preferred having liquidation preference over common, which … I assume … y’all read in the fine print, right?

Wait, also, the liquidation preference is based on the common stock price, that seems kind of wild, actually. It’s one of those things that could be totally normal and just seem wild when you actually stop to think about it (kind of like the depositary agreement that turned out to be a fairly common feature among financial institutions’ issuance of preferred equity units), but this one I can only find in a handful of other companies — one biopharma, one EV, one crowdfunding platform, and one money4gold company — so I’m not sure it’s not a little bit more sus, in reality. This is basically a best-of-both-worlds situation when you have preferred equity units that you think are going to run at a discount to common, which AMC knew theirs might likely do, due to institutional investors being unable to hold derivatives and needing to sell into the market at scale, but then you get to redeem them at common stock prices if there’s a liquidation event? There’s always an angle, I swear. But I digress.

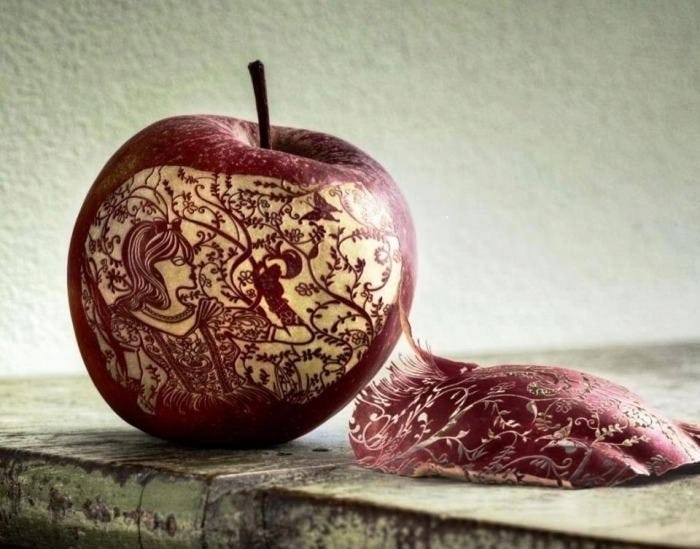

The big takeaway is: there’s more than one way to slice an apple with § 242(d). See, e.g.,

I mean, this doesn’t necessarily sound like something AMC is just going to voluntarily throw themselves into for many reasons, so it would probably be something that Plaintiffs would need to negotiate on behalf of the class, or that the Court would need to suggest (which is perhaps unlikely), or something that … I don’t know, someone would need to raise in the context of a proxy contest that might be imminent, since … you know, tomorrow is July 17th. I hear things on Reddit, but sometimes you all are just talk. There were supposed to be more than twenty-five of you at that settlement hearing.

Also, not for nothing. I learned something the other day when I was researching § 211 that I definitely did not know. Because, to be clear, § 211, this provision cited by a random Twitter person calling for a new board of directors at AMC due to their failure to call an annual meeting, something that’s been bouncing around in the ether for the past few months, as I mentioned — this is not something that regularly gets invoked with respect to publicly-traded companies that have counsel like Weil Gotshal advising them on their legal matters. You know, they usually, uh … take care of such administrivia.

It’s definitely weird that it’s not done. It’s just, like, basic stuff, you know? Uh, have an annual meeting. Yup. Check. And okay, fine, presumably, there is a bit of excuse-y chicken and egg thing going on here, although (to be clear) I do not believe it will not hold an ounce of water with the Court, but I think it goes something like — well, we can’t hold the meeting until the Court rules, because we have a lot to discuss at the meeting about what the Court is going to rule. Well, I think you probably should have just held the meeting and then called a special, kiddos.

But there’s something even weirder about § 211.

When I was researching caselaw on it, which is quite scant due to its rare invocation, so it mostly exists in the closely-held corporation context, I found out something very interesting, which is that the quorum requirement — for reasons that are potentially gameable here in a very weird way — is actually radically reduced when a meeting is ordered under § 211. See for yourselves in MFC Bancorp v. Equidyne Corp., a decision from then-Vice Chancellor Strine, and forgive the ages-old OCR errors, Strine doesn’t actually sometimes use dollar signs in inappropriate places, I’m like 90% sure:

So … as The Dude would say, “that’s [bleeping] interesting, man.” Now, this is where things get really weird because … the quorum requirement normally applicable under the meeting itself, and does not change the requirements for other items called for a vote at the meeting (such as, say … a reverse split), but § 242(d) would do some of the work there, if it is signed into law in advance of its green-light date of August 1, 2023 (there’s no date or schedule for this, and those in the know say that the Governor will get to it when he gets to it — the official status is “Ready for Governor for action”).

But all I can say is … uh, things could get wild?

Also, because there is always one more thing, and because all the other times that I have checked on the Third Amended and Restated Bylaws of AMC Entertainment, Inc., I have not looked at each of the amendments (and because SO STUPIDLY, corporations are not required to file a SINGLE COMPILED DOCUMENT WITH ALL OF THE CONTEMPORARY UPDATES IN ONE SINGLE PLACE WITH THE SEC WHERE I CAN CLICK ON ONE LINK AND SEE ALL OF THE COMBINED UPDATES, UNLESS I AM JUST AN IDIOT AND DON’T KNOW WHERE TO LOOK FOR IT OTHER THAN IN A MILLION LITTLE PIECES), and I did not notice this before, when I was clearly thinking about the ramifications of § 242(d):

AFAICT, this means that after August 1, 2023, AMC is going to be able to:

increase the authorized number of shares of a class of capital stock; or

reclassify by combining the issued shares of a class of capital stock into a lesser number of issued shares of the same class of stock (reverse split);

as long as the votes cast for the amendment exceed the votes cast against the amendment, and

they will also be able to do a forward split to increase headroom with no vote required whatsoever.

The only quorum that will be required is one-third of the outstanding stock. Here’s where they discussed this change that they made to the quorum, in May 2021, in the production documents:

Enlightening, innit? And here:

To zoom back out, though, and be clear, in the event of a meeting ordered under § 211, it appears that not even a one-third quorum would apply, so literally whomever showed up for the vote could be enough, I think? And if it occurs after August 1, 2023, it becomes a free-for-all wherein whatever gets the most votes, wins. No majority of the outstanding required. We go from 50% of the outstanding stockholders required to literally 5 of 10 votes cast can bring home the trophy. That is a radical redesign of Delaware law in a very brief moment, albeit under some very funky quorumstances, admittedly.

Let me tell you something as retail stockholders, if you are still reading and listening. I know that you generally hold yourselves out to be the kind of people who think that voting doesn’t matter, that democracy sucks, that your vote is worthless, that statistically, your vote is unlikely to make a difference, etc. On one level, I suppose that is logical, but in the collective, that’s absolutely idiotic, to be blunt. If everyone adopted that way of thinking, we would lose our democracy; you would lose your voice. It’s not not already happening. Everyone needs to act. That’s why they call it a collective action problem.

But quorum is actually also protective of the corporation in a certain sense. In a meeting without a quorum, if voter turnout is — for whatever reason — insanely high, voters could actually make their desired outcome happen. There are no guardrails to make sure it’s a “valid vote.” It’s a naïve thought, I’m sure, to still believe in democracy, after seeing all the ways in which it has failed us on many levels. And yes, I’m well aware that Stephen Bainbridge is champing at the bit to ride in here and pontificate sagely about how the corporation is not even supposed to be a democracy at all, which I will try to save him some trouble of reiterating by quoting his last summation on the point, wherein he explained that “much of [his] scholarly output over the last several decades has been devoted to the proposition that corporations are not democracies” (emphasis added). I’ll even link to his law review article on the topic to save him the trouble. I get it. We disagree here. I never thought I’d want to go beyond Citizens United, but I don’t just think corporations are people, I think they are entire democracies! (I’m conflating two things for dramatic effect, there is not really a through-line there.)

All this is to say that if you — as a vote-holder — actually, really, truly gave a monkey about corporate governance (and I’m actually, not really wholly convinced by your collective actions that you do) you would probably organize seriously around voting in the next corporate election, whenever that is. Because you could probably make a real difference. But I fear that the point of the various factions here, to the extent that I can understand them, is just to stick it to some other faction for … wanting to make money? Which I am pretty sure (though I could be mistaken) is the but for cause of everyone’s participation in the stock market, but what do I know, I’m just here to nerd out about the law. There’s a reason (there are a multiplicity of them, in fact) that I did not go into finance.

I’m sure I’m missing some minutiae here, because there is a lot going on, and I’m just kind of mulling this all over in my head, playing with it like a kid sipping soda through a Twizzler, and now maybe nibbling at the end a little bit. So, feel free to educate me. I think the biggest “reasons why this will never happen” are all mostly “because it would be abhorrent for business and legal and many other constituency reasons” but I’d love to hear your thoughts.

And to the extent that the company feels victimized by any of this potential democratic action, I just keep thinking of that old saw: “play stupid games, win stupid prizes” — like, everyone needs to think more deeply about what it means to have a radically-differently-constituted stockholder base, because it has implications for brokers and dealers and regulators and companies and court systems, and many, many people in betwixt and between. And while I suppose the same old saw could be applied to the investors, to a certain degree — and I do believe that everyone should take responsibility for the choices and investments that they made — I also think that information disparities are frequently an insurmountable hurdle in our society that no one is doing any blessed thing to fix, and that many people are only taking intentional steps to exacerbate, so until we start to do better, I’m going to do my best to do what I can.

P.S. I feel like maybe I need to brush up on these.

P.P.S. It appears that AMC and its insurers may also be playing a little game of chicken and egg or hide-and-go-seek with the verdict from VCZ, with the insurers filing another extension of time to answer the complaint in the Superior Court until July 21st, although I’m not sure what they are waiting for, or what the end game is, because I don’t know what the settlement dynamics are between insurer and insured here, but we won’t see the insurance companies’ answers until the 21st at the earliest, and something tells me that if we don’t have a decision before then in the main case, we will be more likely to see another extension of time to answer than the Answers themselves. C’est l’assurance, c’est la vie.

Much love,

Chance

P.P.P.S. New ish has come to light:

AMC: This is the [case] that doesn't end... (plus a Tesla settlement surprise)

I asked for help, here: And I so received. Let me make a correction and an addition to last night’s post, above. First, the post suggested one possible alternative universe outcome would be that there could be a reverse split of common and not preferred, allowing the world to perhaps comport more with the FAQ from late 2022 when it answered the question “

![AMC: This is the [case] that doesn't end... (plus a Tesla settlement surprise)](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!fTIP!,w_1300,h_650,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe163ad51-ac25-4223-b688-ce7c09c06a8d_1024x1024.png)

I think you are WAY overthinking the special master's comment about the assumption that APE would need to be invalidated.

I think it is quite simple. You have an action here where conversion benefits APE and the objectors say it hurts AMC (otherwise what the heck are they objecting to?).

Well there are about 900M APE shares and about 500M AMC shares, so I think it is fair to assume that if they were to all vote under the new 242(d) the result would be obvious. The 900M shares whose interest it is to have conversion will win that vote. I don't need to even open my statistics books to know that. So the obvious thing is that any objector insisting that this is all voted again, must also be hoping that somehow the court will invalidate the APE shares, otherwise their objection makes no sense.

On the other point you harp on about diluting APE and never converting... That is not an option. The board originally allowed them to dilute if the share price was over $2 (repeating this from memory so may be off here a bit) and as they diluted the share price fell and the board gave further approval to sell if the share price is over $1. However the share price still fell (to as low as $0.65) when the company barely diluted the stock (fyi, the Antara transaction was a private deal that would have no impact on trading dynamics so we are talking minimal dilution driving the share price down). From an equity viewpoint, the structure at that point was extremely dilutive... Further, there was a very real risk you would see the price fall even further and even with all the preferred shares they would be unable to raise sufficient funds. Also, at some point you still need to have that shareholder vote, when now the vast majority of your shareholders demand that you convert the shares. You can't simply give preference to the desires of AMC holders over APE holders and block the conversion perpetually.

Damn, lawyers really do think of everything haha

I've never worked in the industry so I'm also probably missing a lot of things / wrong somewhere in my beliefs, but the arguments against your alternative that I thought of off the top of my head:

1. Listing fees - from what I know, they are paying additional fees to keep APE listed on the exchange; it might not be much but why spend it if you don't have to, especially with the precariousness of their financials

2. Dilution - Just by the APEs existing, the APE dilution has already been somewhat reflected in the markets; AMC is probably currently trading at much less than the price it would have traded at if APEs were never issued. Even if the alternative path were to be taken, I don't think APEs would go to zero because there is always the optionality of a conversion in the future, so they will always hold some value, and that value is taken from common.

3. Offering dynamics - there probably exists the worry of lack of demand for common in a potential offering because of the looming thought of common/preferred collapse. Who would buy the common when the price would fall if they ever announce the conversion in the future? So maybe this alternative will end up not being value accretive anyway as they have to offer at lower prices for anyone to take a nibble.

IMO, the alternative would mean the company would be taking an L that could, in the worst case, potentially harm their future prospects. That being said, I think the chance for such a path is definitely non-zero.

What's hard for me to grasp from a multitude of standpoints is that before the settlement hearing, I looked through social media just to see what shareholders were saying, and the vibe I got was that most people online actually want the settlement to go through (or for AMC to win through other ways). Given the knowledge of the fractures, both intra- and inter-, within the classes, what would be the "best" way of resolving this shitshow for as many parties as possible (legally or morally)? I still can't think of a good answer.