As I mentioned this weekend, this Substack has a wide-ranging and diverse readership, which we absolutely love and appreciate. Some of you are here for the AMC 🍿 — others for all-things-Musk – yet still another contingent for the erudite words from ye-olde Court of Chancery case law analysis — and another group who just love law no matter the venue — and yet still another who just want to nerd out about something novel and recondite to scratch a random itch at the back of your minds.

Today we’ll cover (1) some quintessential Vice Chancellor Glasscock, (2) Vice Chancellor Laster tackles § 242, (3) an update on all things Musk, including: the Tornetta schedule and plan; reminder on the SolarCity upcoming oral argument (with links to briefing and the watch party); and a quick fly-over to N.D. Cal. for an update on post-trial briefing, expedition, and the reasons therefor, and (4) quick AMC reminders and re-reiterations (along with the tiniest Disney footnote ever, wherein I just barely touch it with an 11 and 1/2-foot pole).

Glasscockian Comeback

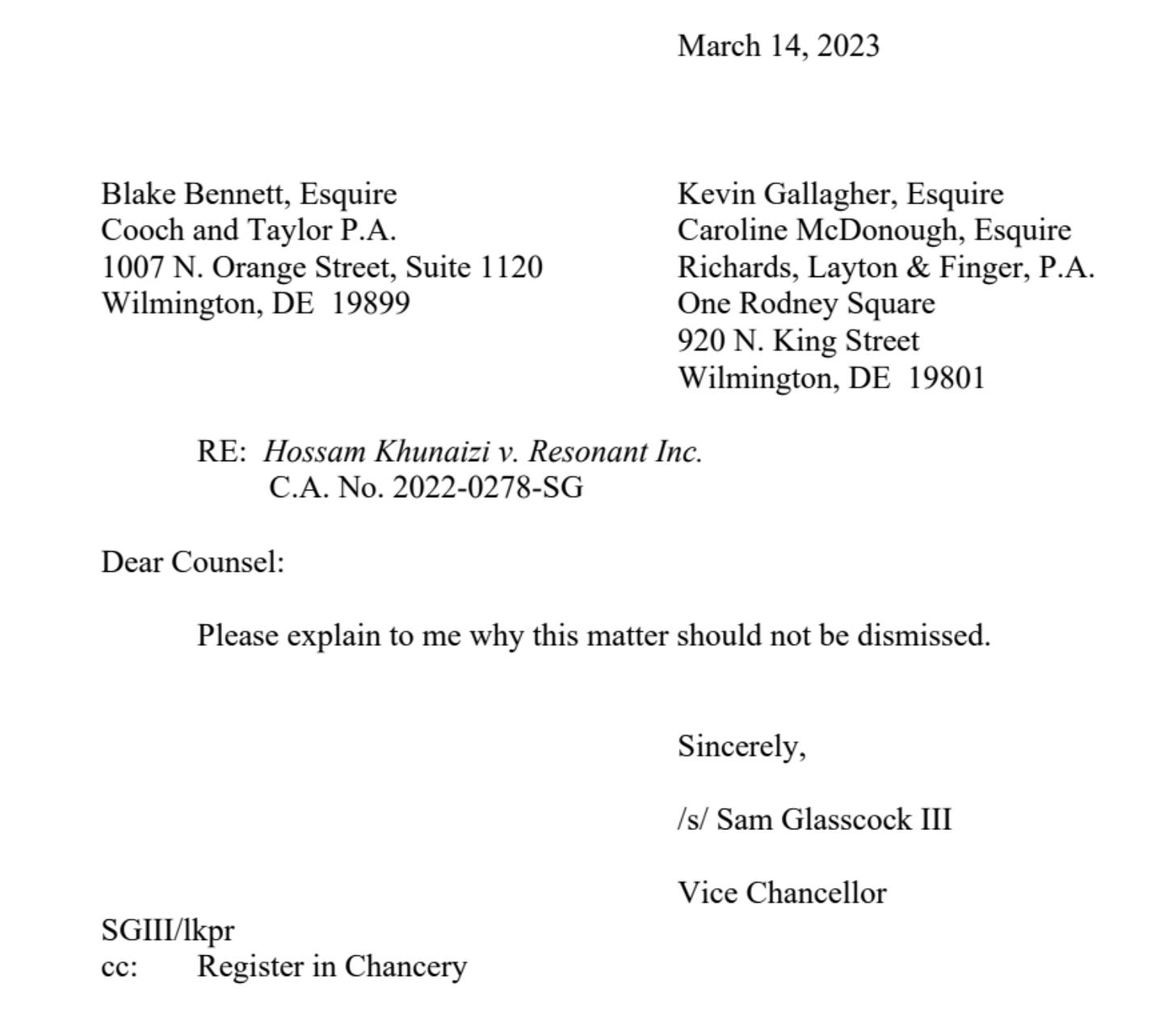

One thing that’s challenging is how much I want to share with the whole world the little inside baseball things about this Court that I love so much but that … might not just immediately make sense without a whole lot of context. For example, Vice Chancellor Glasscock coming out of his convalescence after an accident at his home back in February with this one-liner is such quintessential Glasscockian no-nonsense in the most beautiful way that makes me do the best kind of belly laugh, not because it’s funny, really, but just because it’s so perfect.

I mean, the single sentence letter may not necessarily be funny on its face. The parties stipulated in December that they would update the Court in a month as to the status of the case, and they didn’t do so. So, the Vice Chancellor is simply saying: what gives?

But there’s just something so indefectible about it that I just couldn’t love more, just this je ne sais quoi that makes me break out in giggles every time I read that line. And ok, technically, he sent another slightly-longer letter concerning questionable subject matter jurisdiction in another case just before this one, but the fact that one of his first affirmatively-drafted actions out of the gate, coming back onto the bench out of convalescence is this beaut — it’s just so good.

I don’t know if I can ever do Vice Chancellor Glasscock justice, but it can’t be said I haven’t tried:

All you really need to know about Vice Chancellor Glasscock is that he is the one who — to my knowledge — coined the term autoschadenfreude, which I quoted in one of my absolute first tweets ever back when we had like three followers.

Also, anyone who knows anything about Vice Chancellor Glasscock will know who is speaking in this transcript. 🤣

This is all to say here’s hoping that this little letter means that VCG is feeling better and is back to good health and spirits. Also, it perhaps bears mentioning that C.A. No. 2022-0278 was subsequently dismissed by the parties on March 16th, 2023.

Baader-Meinhof, § 242, and In re Snap

We at The Chancery Daily have repeatedly invoked the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon (also known as "frequency illusion") in reference to our tendency to encounter an issue for the first time in a matter before the Court of Chancery, and then see the same issue arise in other matters soon thereafter.

Well, we are at it again with all things 8 Del C. § 242(b)(2) and I swear to G-d, it is errywhere.

The first place where it came to the foreground was in the three consolidated actions under the heading of In re Snap Inc. Section 242 Litigation (consol.), C.A. No. 2022-1032-JTL, order (Del. Ch. Dec. 14, 2022), although in the intervening months, it has shown up all over the freaking place — mainly in the SPAC-related context, although certainly not exclusively.

But we return to the Snap-context today because there was a hearing in that case this morning, and although we don’t know how the hearing went, I wanted to point out what I think is the absolute best of this Court, first to humble brag on a process point, but also to share an absolutely fascinating and revelatory content piece put out by Vice Chancellor Laster last week for those of you who might be in the weeds on the § 242 issues.

One of the things I find endlessly incredible about this Court is the superhuman amount of work product that the actual humans running the Court manage to produce. But not only is the production volume amazing, its content’s quality is what really blows my mind. In a span of seven days earlier this month, Vice Chancellor Laster and Chancellor McCormick put out a combined 273 pages across three opinions that have wide-ranging implications across myriad areas of corporate law.

Today’s TCD Long Form details no less than eight areas that VCL addresses with interesting or novel notes in just the Fugue opinion — and that’s in dicta alone! No doubt hundreds of pages of commentary will be written digesting the content of those three opinions, and dozens of hours will be spent in discussion thereof. Many have surmised that much of the upcoming 35th Annual Tulane Corporate Law Institute later this week will likely be dedicated to chatter around the In re Mindbody decision and its implications. We’ll be bringing you the highlights from the sessions, although I assume most of the Mindbody talk will be relegated to unplanned time, given the proximity of its issuance to the conference’s start.

But the best of the Court is how much attention the judges give to the cases not only in their disposition, but also during their pendency. It’s one thing for a judge to take the time to process the case once it’s been tried and presented by competent counsel. In my opinion, it’s another thing altogether for a judge to manage to get their hands dirty during the litigation to sufficiently grok the issues, such that competent counsel can fully address all the issues in a dialectic fashion with the Court, such that everyone can truly be said to have hashed things out. Those of you who are “new here” have gotten a sense of this with the Tornetta case, in the way that Chancellor McCormick has asked for supplemental briefing on some novel and thorny issues. She guided the supplemental briefing both in oral argument with questioning of her own, and with a follow-up letter, which both provided guidance but also flexibility for the parties to litigate as they saw fit.

On Friday, we saw another example of this in the consolidated Snap cases from Vice Chancellor Laster, this time in the form of a long and detailed letter to the parties’ counsel in advance of this morning’s oral argument. And it provides intricate guidance and insight into his thinking about the issues at play in the case, and the outline for a set of hypotheticals the parties were hopefully prepared to discuss during argument. Although it’s long, I quote it here in full because I can’t find any extraneous parts to omit. I really love the “Let’s emphasize…” and “Let’s de-emphasize…” framework, it’s very Lasterian.

Dear Counsel:

I write to provide some areas that I would ask counsel to either emphasize or de- emphasize for the hearing on Monday, March 20, 2023.

Let’s de-emphasize the debate over whether the Officer Exculpation Amendment is a good or bad idea. The merits of the amendment are not at issue in this case. Personally, I can see how reasonable minds could take either side of the issue.

Let’s de-emphasize the purported distinction between rights of stockholders and rights that are associated with shares such that the right to sue for breach of fiduciary duty is an example of the former and not potentially subject to Section 242(b)(2). I do not see how that distinction survives under Urdan v. WR Capital Partners, LLC, 244 A.3d 668, 677–79 (Del. 2020), and In re Activision Blizzard Inc. Stockholder Litigation, 124 A.3d, 1025, 1050, 1056 (Del. Ch. 2015).

Let’s de-emphasize the debate over whether the Officer Exculpation Amendment alters the right to sue by eliminating the ability to recover damages. It seems to me that the certificate of incorporation previously accommodated a right to sue that had a particular scope. The Officer Exculpation Amendment reduced that scope. Except that the right to sue was implied and not express, the reduction is no different than an amendment that reduces a liquidation preference from $100 to $90 per share, or an amendment that replaces a redemption right that requires payment in cash with a redemption right that requires payment of at least 90% in cash and permits the balance to be paid with a note. In each case, there is a reduction in the scope of the right, and the reduction is adverse precisely because it is a reduction. The question is simply, “What are the implications of that reduction for purposes of Section 242(b)(2)?”

Let’s de-emphasize the debate over whether there is a meaningful, plain-language distinction between “powers” and “rights.” It seems to me that courts and commentators, myself included, can refer colloquially to stockholders having three fundamental rights—the rights to vote, sell, and sue—without excluding that those concepts might formally and properly be conceived of as “powers” for purposes of corporate law analysis. The plaintiffs have cited a number of statutory sections that refer to the ability to sue as a power, and although the defendants have tried to distinguish the context of those sections, it remains true that the DGCL regularly refers to the ability to sue as a “power.” It seems to me that the real debate here is over whether Section 242(b)(2) only applies to special powers, viz., powers that go beyond the default rights that all shares carry, or whether it also applies to reductions in the baseline powers associated with shares. Put differently, does the right that is subject to reduction have to start out as extra to implicate Section 242(b)(2), or can it start out as basic?

Let’s emphasize the possible types of amendments that could implicate Section 242(b)(2) under the plaintiffs’ approach. The plaintiffs have cited one involving the imposition of a transfer restriction. The defendants tried to dodge this example by positing that only Section 202(b) would apply to this amendment and not Section 242(b)(2). I would think that both statutes would apply, with the validity of the amendment governed by Section 242 and its enforceability against a particular stockholder governed by Section 202(b). The defendants also tried to dodge this example by positing that alienability is a function of the common law and therefore not a power or right of the shares. Section 159 states that shares are personal properly and “transferable as provided in Article 8 of subtitle I of Title 6.” I would like the defendants to engage with the plaintiffs’ example on the assumption that Section 242(b)(2) applies.

The defendants have cited other examples, and I would like the plaintiff to engage with them. For example, under the plaintiffs’ reasoning, why would a charter amendment eliminating the right to act by written consent not require a class vote? Or a charter amendment approving a conversion to a private benefit corporation in light of the change in the scope of the directors’ managerial duties and the ability of a stockholder to sue for breach of those duties under Section 365?

The defendants also point to a charter amendment implementing a forum- selection provision, and that type of provision warrants some discussion. One possibility is that a charter amendment that implements a provision that can appear in the bylaws cannot constitute an adverse change sufficient to trigger a class vote under Section 242(b)(2). When approving a bylaw-based forum selection provision, the Chevron decision drew on the distinction between bylaws that validly established procedural requirements on stockholder rights, which could appear in the bylaws, and those that invalidly attempted to impose substantive limitations on stockholder rights, which had to appear in the charter. Boilermakers Local 154 Ret. Fund v. Chevron Corp., 73 A.3d 934, 951–52 (Del. Ch. 2013) (citing CA, Inc. v. AFSCME Empls. Pension Plan, 953 A.2d 227, 236–37 (Del. 2008). I have suggested that the same distinction, such that “a substantive limitation must appear in the charter; a procedural regulation can appear in the bylaws.” Sciabacucchi v. Salzberg, 2018 WL 6719718, at *8 n.49 (Del. Ch. Dec. 19, 2018) (citations omitted), rev’d on other grounds, 227 A.3d 102 (Del. 2020). Under that approach, if a provision is sufficiently procedural to appear in the bylaws, then it is not a substantive change in a power or right. Section 115 authorizes a forum-selection provision to appear in the bylaws. Under that reasoning, Section 115 has removed forum-selection provisions from the ambit of provisions potentially subject to a class vote under Section 242(b)(2). Does that distinction take the forum-selection provision off the table as an analogy for our case?

Footnote: Before the adoption of Section 115, I worried that a forum-selection provision limiting stockholder litigation had to appear in the certificate of incorporation, precisely because it imposed a limitation on the right (or power) to sue, and I therefore initially proposed only “charter provisions selecting an exclusive forum for intra-entity disputes.” In re Revlon, Inc. S’holders Litig., 990 A.2d 940, 960 & n. 8 (Del. Ch. 2010). As I later explained, Section 115 eliminated that concern by authorizing both charter-based and bylaw-based forum-selection provisions, rendering moot any concern about Sections 102(a)(4) or 151 for these clauses. Sciabacucchi, 2018 WL 6719718, at *8 n.49.

Let’s emphasize and consider whether Section 242(b)(2) only applies to express powers and rights in the charter that are special and extra. There are other important stockholder rights that are present as a matter of law, even if the charter is silent, including not only the three principal powers (the right to vote, the right to sell, and the right to sue), but also more specific rights, such as the right to obtain books and records or the right to force a corporation to hold an annual meeting or the right to seek appraisal. Might the language of Section 242(b)(2) address reductions in the scope of the actual powers and rights granted to and carried by the shares, regardless of whether those powers and rights exist expressly in the charter or as a matter of law? The only difference is the visibility of the baseline right and hence the reduction in scope. If the actual powers and rights are special and extra, then any reduction is obvious when the scope of the power or right is reduced. But if those powers and rights are established by law, they still exist. Why would a reduction in the actual rights associated with that security not warrant a class vote under Section 242(b)(2)?

Let’s emphasize Hartford Accident & Indemnity Co. v. W.S. Dickey Clay Manufacturing Co., 24 A.2d 315 (Del. 1942), and Orban v. Field, 1993 WL 547187 (Del. Ch. Apr. 1, 1997), which are clearly the key cases. Both admittedly contain language about special rights (I would prefer to de-emphasize the word “peculiar” given its historical associations with the antebellum South’s “peculiar institution”). Neither Dickey Clay nor Orban dealt with an amendment that changed an express or special power or right or sought to reduce a default right below the default. Both dealt with relative rights. Dickey Clay addressed the relative priorities of shares in the capital structure. Orban addressed the dilution of voting rights through the issuance of more shares of common stock. To what extent do the holdings in Dickey Clay and Orban speak to an amendment like the Officer Exculpation Amendment that works an actual reduction in the scope of a default right?

Let’s also focus on the parties’ key arguments. The plaintiffs make a straightforward plain language argument about why Section 242(b)(2) applies. The defendants respond with three arguments that would foreclose the plain language approach and which they deploy to argue that no class vote is required for the Officer Exculpation Amendment.

First, they say that the Officer Exculpation Amendment cannot trigger a class vote under Section 242(b)(2) because it is not a power or right expressly set forth in the certificate of incorporation but rather a power or right implied by law. The generalized proposition is that Section 242(b)(2) only applies to powers or rights expressly set forth in the certificate of incorporation. Let’s call this the Express Power Argument.

Second, they say that the Officer Exculpation Amendment cannot trigger a class vote under Section 242(b)(2) because it is not a special power, privilege or right, which seems to mean the type of extra power, privilege, or right associated with preferred stock and not shared by all stockholders as a matter of default principles of law. The generalized proposition is that Section 242(b)(2) only applies to extra powers, privileges or rights, beyond what stockholders possess as a baseline. Let’s call this the Special Power Argument.

Third, they say that the Officer Exculpation Amendment cannot trigger a class vote under Section 242(b)(2) because it applies equally to all types of stock. The generalized proposition asserts that Section 242(b)(2) only applies when an amendment targets one class of stock. Let’s call this the Different Treatment Argument.

All three arguments apply to the Officer Exculpation Amendment. Is that necessary to avoid triggering a class vote under Section 242(b)(2)? What if only one or two applied? Does it matter which?

Using examples that implicate the stockholders three basic powers or rights—to vote, to sell, and to sue—I have tried to stress test these arguments. Each hypothetical is designed to eliminate one or two of the defendants’ three arguments. It may be helpful to discuss some or all of them during oral argument.

1. Assume that a certificate of incorporation provides for a class of common stock and specifies expressly that it carries 1 vote per share, which is the same number of votes the shares would have by default under Section 212(a). Assume that the certificate of incorporation provides for a class of preferred stock and specifies expressly that it carries 1 vote per share, which again is the same number of votes the shares would have by default under Section 212(a). The classes vote together on all issues. Assume that the corporation has issued shares of both classes. Assume that the corporation proposes a charter amendment to eliminate on the right of the preferred stock to vote in the election of directors.

How do the Special Power Argument, the Express Power Argument, and the Different Treatment Argument apply to this hypothetical?

Does Section 242(b)(2) require a class vote? Is the analysis different if the corporation proposes a charter amendment to modify the voting rights of the common stock and not the preferred stock?Assume that same capital structure as in Hypothetical 1, except that the certificate of incorporation also provides that each class of stock has a special right to a separate class vote on any merger. Assume that the corporation proposes a charter amendment to eliminate the separate class vote entirely, so that no classes of stock will enjoy it.

How do the Special Power Argument, the Express Power Argument, and the Different Treatment Argument apply to this hypothetical?

Does Section 242(b)(2) require a class vote of the preferred stock or the common stock?The voting rights of common stock do not have to be set forth in the certificate of incorporation under Section 102(a)(4). Section 212(a) provides that “[u]nless otherwise provided in the certificate of incorporation and subject to Section 213 of this title, each stockholder shall be entitled to 1 vote for each share of capital stock held by such stockholder.” Assume that a certificate of incorporation provides for a class of common stock and a class of preferred stock but is silent as to voting rights. Each share therefore carries 1 vote, and the classes vote together on all issues. Assume that the corporation has issued shares of both classes. Assume that the corporation subsequently proposes a charter amendment to eliminate the voting rights of the preferred stock.

How do the Special Power Argument, the Express Power Argument, and the Different Treatment Argument apply to this hypothetical?

Does Section 242(b)(2) require a class vote of the preferred stock? Is the analysis different if the corporation proposes a charter amendment to modify the voting rights of the common stock and not the preferred stock?Assume that a certificate of incorporation provides for a class of common stock and a class of preferred stock and does not specify any transfer restrictions. The corporation’s shares are therefore freely alienable under Section 159. Assume that the corporation has issued shares of both classes. Assume that the corporation proposes a charter amendment to impose a right of first refusal in favor of the corporation on the preferred stock.

How do the Special Power Argument, the Express Power Argument, and the Different Treatment Argument apply to this hypothetical?

Assuming Section 242 applies and that alienability is a power associated with shares, would Section 242(b)(2) require a class vote of the preferred stock?

Is the analysis different if the corporation proposes to impose the same transfer restriction on the common stock rather than the preferred stock? What if the corporation proposes to impose the transfer restriction on both classes of stock?Assume that a certificate of incorporation provides for a class of common stock and a class of preferred stock. Assume that the certificate of incorporation provides as a special right that if any stockholder proposes to sell, then any existing stockholder of either class can exercise a right of first refusal, with the shares divided pro rata among exercising stockholders. Assume that the corporation has issued shares of both classes. Assume that the corporation proposes a charter amendment to eliminate the express and special right of first refusal for all stockholders.

How do the Special Power Argument, the Express Power Argument, and the Different Treatment Argument apply to this hypothetical?

Does Section 242(b)(2) require a class vote of the preferred stock or the common stock?Assume that a certificate of incorporation provides for a class of common stock and a class of preferred stock and does not specify any transfer restrictions. Assume that the certificate of incorporation states affirmatively that a stockholder can sell to any third party who is not a competitor and cannot sell to a third party that is a competitor. Assume that the corporation has issued shares of both classes. Assume that the corporation proposes a charter amendment to impose a right of first refusal in favor of the corporation on any sale to a third party who is not a competitor.

How do the Special Power Argument, the Express Power Argument, and the Different Treatment Argument apply to this hypothetical?

Assume that Section 242 would apply and that alienability is an attribute of the shares under Section 159. Does Section 242(b)(2) require a class vote of the preferred stock or the common stock?Assume that a certificate of incorporation authorizes both common stock and preferred stock and that the corporation has issued shares of both classes. Assume that the corporation does not have a traditional, director- oriented Section 102(b)(7) provision in its certificate of incorporation. Assume that the corporation proposes to “limit[] the personal liability of a director ... to the corporation or its stockholders for monetary damages for breach of fiduciary duty” by providing that the director will not have liability to the holders of the preferred stock, except for the exclusions set forth in Section 102(b)(7).

How do the Special Power Argument, the Express Power Argument, and the Different Treatment Argument apply to this hypothetical?

Does Section 242(b)(2) require a class vote of the preferred stock? Is the analysis different if the corporation proposes a charter amendment to modify the power to sue of the common stock and not the preferred stock?Assume that a certificate of incorporation authorizes both common stock and preferred stock and that the corporation has issued shares of both. Assume that the corporation proposes to adopt an amendment which requires that any common stockholder must own at least 10% of the corporation’s outstanding shares of common stock before the stockholder can sue individually or derivatively.

How do the Special Power Argument, the Express Power Argument, and the Different Treatment Argument apply to this hypothetical?

Does Section 242(b)(2) require a class vote of the preferred stock? Is the analysis different if the corporation proposes a charter amendment to modify the power to sue of the common stock and not the preferred stock?In each of these cases, the premise that the reduction in an existing power or right triggers a class vote would be sufficient to require a class vote under Section 242(b)(2). The plaintiffs would argue that the plain language of Section 242(b)(2) dictates that result by referring to an adverse alteration or change in the powers associated with the class of stock. Why is that an undesirable result?

Finally, I ask that the defendants prepare and submit a chart comparable to what appears on page 12 of their brief which provides both raw numbers and percentages based on the number of shares outstanding. Under Section 242, that is the denominator. The votes cast figure is irrelevant and misleading.

I look forward to discussing these issues with you.

Sincerely yours,

J. Travis Laster

J. Travis Laster

Vice Chancellor

There’s a lot to digest there, and it will be interesting to see how well the parties used the weekend to hew their arguments to the Vice Chancellor’s requests for emphasis and de-emphasis, and to prepare for his very clear hypotheticals. There will be no argument available for a response of “I’ll have to get back to you on that, Your Honor.”

But as to you-all, and all the above, I will definitely have to get back to you on what I think it all means, especially until after I’ve seen the transcript from this morning’s oral argument, and maybe even until after I’ve seen the ruling on the motion for summary judgment.

In erm, other news…

Yes, that’s a joke. Elon’s middle name is Reeve, but erm is also the noise that I make when someone asks me to report on what’s going on with Musk’s multifarious (it only rhymes with nefarious) litigations, as in, erm, urgh, some other glottal, guttural sound as I try to squirm out of doing it: as in, do I have to?

Ok, yes, fine! We’ll do a refresher.

We have the supplemental briefing from defendant in Tornetta that came in last week. I am digesting what substance there is of it, and will probably be writing something up in this pages this week. Unless I get through it and decide that it’s just worth waiting until the end of the month when the plaintiff’s response comes out instead. I will keep you posted.

As a reminder, here’s the briefing schedule. Once the final act is done (i.e., ten days after April 11, 2023, so April 21, 2023), the case will probably be “taken under advisement” (unless further oral argument is requested), which would put the timeline for decision somewhere out in late summer, assuming there are no further supplemental supplemental supplemental requests.

In other Musk news, I found this tidbit from the N.D. Cal. Tesla “420” post-trial docket interesting. Plaintiff wants to renew their Rule 50(b) motion for judgment as a matter of law in combination with a Rule 59 motion (for a new trial) — I’m pretty sure this has to do with an argument that the jury was improperly instructed on the prior ruling on recklessness and scienter and on the burden of proof afaict. But note the very quotidienne, real world rationale for the compressed briefing to be done by the end of the month, but the fact that the argument still won’t take place until April 6th. So, the clerk will be gone, but the motion will carry on…

Reminder that the Solarcity appeal will be heard by the Delaware Supreme Court on March 29th at 10:00am Eastern. You can watch the hearing live here:

If you’d like to read the appeal briefs, you can do so:

I’ll be live-tooting the event here.

&etc. 🍿

As far as other non-Musk, high-profile items, the AMC case continues to roll along in the background, here’s a reminder on the schedule, and another time I’ll say: the Court is not going to rule on a motion to dismiss before the Preliminary Injunction hearing. Nor is she going to rule on the motion to dismiss at the Preliminary Injunction hearing because it won’t have been briefed. I promise. She’s going to rule on the Preliminary Injunction at (or after) the Preliminary Injunction hearing.

The two-hour Disney books and records trial also happened on March 15th before Vice Chancellor Will. I haven’t quite worked out how to say anything about it without saying something that sounds like I’m saying something I’m not necessarily tryna say. There are a lotsa ins, lotsa outs, lotsa whathaveyous.

But can we all agree that this is a jocose clip from the § 220 plaintiff’s deposition?

If not, perhaps try it like this. I do think you will find it quite waggish in its own way.

/scene

P.S. If you (still) don’t know what a books and records action is, you can read this tweet thread, which I should definitely turn into a longer and easier to read Substack post that doesn’t require going to Twitter! Thanks for the suggestion! 😂